Game AI - the use of AI for gameplay - is facing a real test to its future.

The games industry’s frameworks for knowledge exchange continue to be fraught and fail to sustain themselves.

The industry relies too much on individuals who advocate for these ideals.

Without collective ownership, we’re at the whim of commercial need.

The AI and Games Newsletter brings concise and informative discussion on artificial intelligence for video games each and every week. Plus summarising all of our content released across various channels, like our YouTube videos and in-person events like the AI and Games Conference.

You can subscribe to and support AI and Games, with weekly editions appearing in your inbox. If you'd like to work with us on your own games projects, please check out our consulting services. To sponsor, please visit the dedicated sponsorship page.

Hello and welcome (back) to AI and Games. After what’s been a very busy couple of weeks on this here publication, it’s time to get back to what is for me the most important piece I’ve been working on this year.

But before we do…

This Issue is Sponsored by nunu.ai

Special thanks to the team at nunu.ai who have sponsored our final big issue of 2026.

nunu.ai builds AI agents to test and play games. Game studios use nunu to automate manual testing and accelerate their QA cycles. Our agents perform human-like testing from natural language instructions and deliver precise insights, recordings and reports.

Schedule a call to try it out: https://calendly.com/jan-nunu/30min

Join our Wrapped Livestream

A quick reminder that our end of year livestream and QnA will be hosted this Friday, December 19th @ 4pm GMT (16:00) on YouTube. Come by as Shraddha and I walk you through the year, the newsletter, our YouTube, client projects, Goal State, the conference, and answering your questions!

Game AI’s Existential Crisis Part II: Ensuring Access to Knowledge & Skills

At the end of October I published the first part of my essay on Game AI’s existential crisis. A longform breakdown of the current challenges facing the adoption of artificial intelligence for gameplay in the current video game market. As discussed in that initial article, I believe we have three distinct areas of concern that as a community we need to be addressing:

The challenges faced by Game AI as a field, in ensuring we address the ever increasing demands on contemporary game design and development.

How education and access to knowledge is a challenge both for the existing community and for new generations of developers.

Issues faced in building and maintaining a community for developers around the world.

In part one I gave a broader introduction to the subject matter for those new to game AI, and tackled the challenges the field faces on a technical and design level. I’m pleased to say that this received a positive response upon release. While I’m dealing with a difficult subject, and in a far from positive light, it was great to see many from across our community whose work I admire and opinions I respect align with the issues raised. Perhaps critically, the most useful aspect of this was a sense of confirmation: that the feelings that have been slowly eating away at me for close to two years were shared.

For this second part, I want to focus on the perils of education, and this is an equally complicated matter, and one that I have now tackled from various angles across this hodgepodge of stuff one might call a career these past 15 years, including:

10 years as a member of staff in Higher Education (i.e. university), reaching a position of senior lecturer and course director at several UK universities. During that time I taught and led undergraduate and postgraduate courses in computer science, artificial intelligence, and game development. Both being nominated for and winning institutional and national awards for my work.

An external examiner and moderator to university courses and PhD programmes in the UK and overseas. Plus acting on industry advisory boards for UK educational programmes such as IGGI based at University of York and Queen Mary University of London.

A former STEM ambassador in the UK, participating in events with school kids of various ages.

A former academic researcher with over 60 peer-reviewed publications in areas of artificial intelligence in and around game development. Including work in supporting the organisation and running of workshops and conferences.

A volunteer track chair at the nucl.ai conference in 2015 and 2016.

A member of the advisory board to the GDC AI Summit from 2020 to 2025.

A public speaker invited to events around the world to discuss AI in and around the video games industry.

My current work as a professional trainer and consultant to a variety of games studios and other creative businesses around the world.

Lead organiser of the AI and Games Conference, now the largest even on AI in the games industry in Europe, and one of the largest independently-owned events of its kind in the world.

And of course, the writer, voice, and creator of the AI and Games YouTube channel, which has over 220,000 subscribers, and has accrued over 15 million views since the first video launched in 2014.

Now I appreciate that list reads like a bit of a flex, it really wasn’t my intent - admittedly it’s a longer list than I anticipated - but… my point is I have spent my adult life committed to teaching others. Even when I reached a point where my frustrations with higher education led to my leaving academia, I have continued to build towards finding my own way to connect with and inform others be it through public engagement, our conference, our publications (including this here newsletter), and of course our online courses we hope to start rolling out in 2026.

As a result of these experiences, both working inside and outside traditional educational systems - not to mention supporting dissemination within the video games industry - I think a lot about how education works both prior to and during our professional careers, and this guides a lot of my perspectives in this second instalment.

To the point, my focus in this entry is on the following key issues:

Providing access to information and knowledge continues to be a key issue.

Finding relevant and useful information is becoming increasingly more difficult.

Our field’s over-reliance on individuals to support and sustain the sector.

How shifting trends in education are negatively affecting game AI as a field.

How we empower junior developers to excel is increasingly demanding.

You’ll notice that a lot of the issues I raise are uniform across the games industry, but we will get into more game AI specific topics throughout.

Follow AI and Games on: BlueSky | YouTube | LinkedIn | TikTok

Our Access to Information is Fraught

This will not be a surprise to anyone who works in the games industry itself, but how we consolidate and retain knowledge is a big problem. I figured let’s kick this part into high gear with a bit of a deep-dive into how a lot of this works.

Knowledge exchange in games is often limited by virtue of the sector’s ongoing sense of secrecy. The games industry from the very beginning has acted as a mechanism for commercial product first, a technical innovation second, and as a creative medium in distant third. Given its technological roots, so much of video games as an industry emerged from individuals or small teams hacking away at their respective projects. With knowledge exchange largely achieved by meeting other developers at events and having a chat and keeping those contacts flowing.

While pretty awesome, it means that it never really had this main flow channel through which knowledge could be shared. This ever running conflict between being an artistic medium and technological innovator, has meant that we have repeatedly kept both emerging talent, as well as audiences, at arms length as to how the sausage is made. This has, in my opinion, led to numerous issues in the sector, including:

A failure to create institutions that consolidate our history and knowledge.

A failure to disseminate knowledge for professionals in the sector without barriers.

A failure to engage more broadly with both consumers and aspiring professionals.

Compare this to other creative or technology-based disciplines share how products are built or creative ideas are expressed and I think both the information within our industry as well as outside of it is poorly communicated and consolidated. Cultural institutions such as the BFI and BAFTA in the UK have began to support games, and it’s part of a gradual realisation that cultivation of expertise in games helps create a culture that normalises the discussion around processes of how these projects are made. But it’s been a long battle to reach even this point, given the odious argument of whether games could be considered art akin to these other formats kept getting in the way - an issue only made worse by the industry’s largest and most commercial hungry entities.

A Lack of Institutions for Distributing Knowledge

As a result of this commercial focus, much of the knowledge distribution platforms in the games industry are consolidated through larger events. This can include the likes of B2B (business-to-business) events like the Game Developer’s Conference (GDC) in the US plus regional events like Develop in the UK. Plus there are B2C (business-to-consumer) events like Gamescom (which has its own B2B event, Devcom, attached to it) or the ill-fated EGX events in the UK.

Our ability to share knowledge and build community - which is the focus of part three - is often inherently tied into the business of game development and consumerism itself. Sadly the idea of sharing information of how games are made as a concept in and of itself is incredibly rare. Opportunities to enrich the sector and even educate our players, have never been considered a primary focus - and often struggle to mature or develop lest there is a broader B2B or B2C focus to monetise.

While when I discuss knowledge distribution I particularly think of events, books and similar publications are equally relevant. Though sadly they are often more fickle than the physical events: publishers for print materials largely come and go and there is little effort to retain consistency outside of individual authors - a point I will return to later. Speaking more specifically of game AI, we have a handful of books and series that exist, and we’re grateful for them. But they are sadly sporadic, rarely consolidated, and frequently out of print.

A Closed and Inaccessible Culture

As a result of this ecosystem, we often struggle to find ways to share information from one studio to another. Developers are often trying to find out what their peers are doing, and even when we try to contribute, engage and share, that is a challenge in and of itself. Attending conferences much less presenting at them can be difficult for a variety of socio-economic reasons, and even writing the talks has its own challenges.

The Bureaucracy of Secrecy

Given the philosophy of treating games as commercial products first and foremost, as an industry we’re keen to obfuscate the processes of development as much as possible. While there are many people who are keen to engage with the broader development community, be it through books or conferences, there are a variety of issues that often impede this, and quite often the largest of these issues is bureaucratic.

The secrecy of the games industry means it can be difficult to get authorisation to get your information out there. Quite often it comes back to the ability to show the team is doing something really innovative, and therefore it helps the company look good. But even then that message is being carefully constructed, and what little materials that are shared are limited.

Believe me the level of oversight that goes into getting even a 20-second clip of in-engine development footage to be released publicly can be significant. Particularly when there are partners involved (e.g. licensors). I can speak to numerous examples be it in book chapters, GDC talks, and even our own output where we’ve had lengthy email threads for weeks at a time with comms and legal to try and support the case for why showing a handful of short clips or image of in-engine asset is valuable for this output. The studio was concerned what liabilities this could bring to all parties involved, rather than the broader message the talk was providing - even when quite often there really isn't anything to worry about.

Editorial Note: Let me stress while I consider this a failure of the sector as an entity, this does not reflect in any way on those who work in communications and PR at games studios. Working in comms is a very challenging role, and the folks in this space are often some of the nicest people in game development. My love to you all!

Events and Gatekeeping

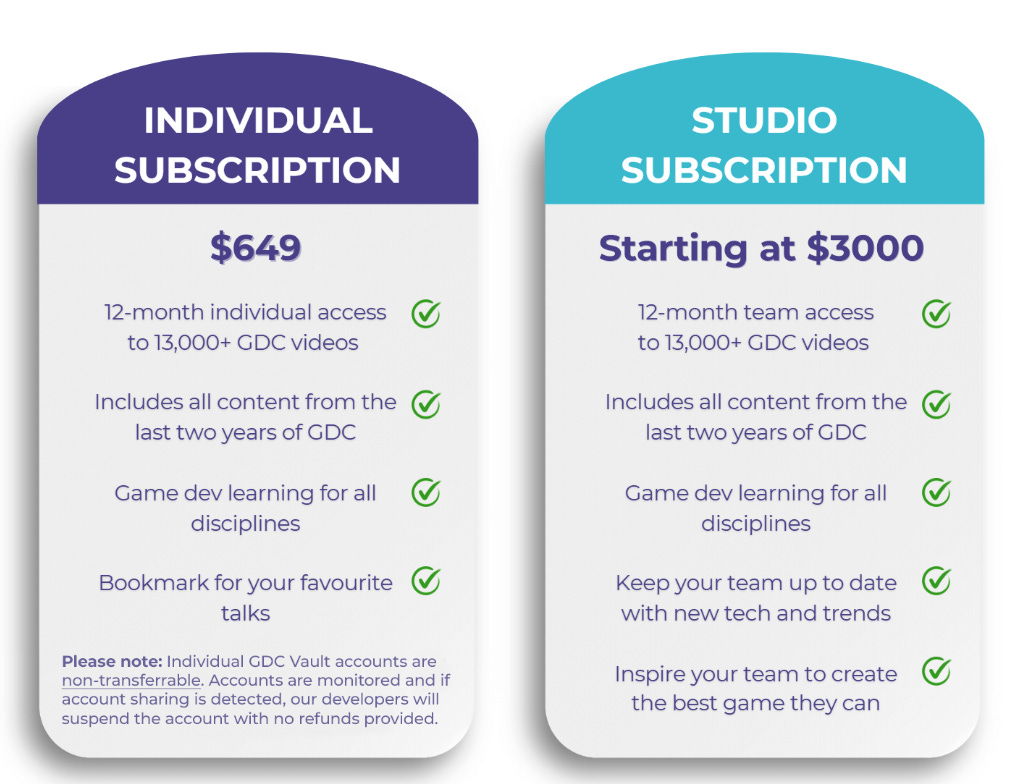

While I argue for the value of conferences - after all I run one now - they are still the most aggressive examples of gatekeeping knowledge. Events such as GDC often charge exorbitant prices for even junior developers to attend, and keep the bulk of their library in the ‘vault’, which equally carries an expensive price tag.

The decision on how this information is collated and released in the future and disseminated to public audiences is in many instances driven by profit rather than supporting the community. It reinforces that being at the event is paramount and if you missed the talks that’s on you.

Now of course I understand the need to charge for costs as you run a developer event. Believe me, I was rather stressed watching our 2025 budget go up, and up, and up, but there is a difference between covering costs and turning a reasonable profit versus gouging your audience.

GDC’s owner Informa is a multi-billion pound corporation that runs a variety of events worldwide, and relies heavily on gatekeeping information by relying on the sentiment that their events are the place for professionals to converge. Introducing a real FOMO aspect to their portfolio. It doesn’t really need the cash from selling vault subscriptions, but it still does it and at exorbitant cost: $649 for individuals, and $3000 or higher for studios per year.

By the way, full disclosure: the AI and Games Conference releases talks for free afterwards. We don’t do it straight away - given we’re a small team and editing the videos takes time - but the vast majority of the material shown at our events is made available for everyone to enjoy. In addition, we actively work to keep the ticket prices as low as we can - including working with sponsors to subsidise ticket prices for students and indies.

But even now as GDC is struggling, with marketing and company spend dropping and attendance failing to reach pre-COVID levels, the recent rebrand to the ‘Festival of Gaming’ has failed to meaningfully reduce the entry costs. While the pricing tiers have been flattened out somewhat, it has done nothing to support entry-level developers participating who are on limited budgets. Meanwhile suggestions (even coming from advisory board members such as myself) of offering more financial support or even remote participation have largely been ignored.

It’s an outdated and outmoded approach to the conservation of knowledge which I believe is one of the root causes of many of the industry’s current problems. Plus as we’ll discuss shortly, GDC’s recent efforts is a great example of how when B2B side of the event struggles, access to and quality of knowledge exchange is affected as a result.

Failure to Engage with Consumers

A mild tangent from my broader point, but one that is quite relevant. I think a lot of issues inherent within gaming culture also stem from this effort to obfuscate how video games are made. It’s not just that we limit the number of avenues in which game development processes are shared, but we refuse to engage in broader discourse with the consumer - and that has led to a tense relationship with our audience.

Games studios are keen to make a lot of noise about what an impending release will look like - be it the features, the experience being crafted for players, the story, the characters and much more besides - but then we refrain from talking about how we made it, even after it shipped.

It’s not common to discuss how game development works, because in truth it’s a rather ugly process. As much as games has historically hoped to be considered akin to the likes of film and television, this in the long run has done it a disservice. Given far too often consumers think these two things are rather similar, when in reality they’re quite different. Games as products continue to evolve as they are being made, decisions are made that fundamentally change the final product, and all the while we’re working towards bringing a lot of disparate threads together at the last minute hoping it will all work out as envisaged. Naturally this makes it difficult to market a game during the build-up, and as such the consensus is largely to keep the door slammed shut and not discuss the game until it is ready for pre-order.

I have a separate essay to write on this one day - though I did make a video about it a few years back - in that I think a significant amount of the issues the games industry has in perceptions of developers within ‘gamer’ culture stems from this fundamental failure to be more open about how games are made, and frankly I think it’s too late for that to be rectified.

The Added Challenges for Game AI

Having laid some groundwork here, I wanted to focus specifically on Game AI now. All of these issues are critical to us, and then some. After all as discussed back in part one Game AI is very much its own beast. We exist both in the broader motions of the video games industry, while also being a curio within artificial intelligence itself. Plus as mentioned in part one, it is a sector that often still uses ‘older’ techniques to solve contemporary problems.

As a result, there is an ever increasing need for Game AI insights to be disseminated more broadly, and it falls under a number of categories:

To reaffirm the focus of Game AI and how it remains unique.

To highlight the unresolved challenges faced by the sector.

To reinforce (and reintroduce) techniques as valid solutions to known problems.

To build stronger links within a dwindling community in context of broader AI.

To reinforce links between studios, research labs, and other academic partners.

The first of these points I feel is largely self-explanatory, though I will highlight that almost every single talk I deliver in the games industry often starts with my clarifying this issue. Because most players, heck most game developers, don’t know what Game AI is. Particularly as the term AI has become associated predominantly with machine learning and generative AI in the broader consciousness.

But also returning to my point of using old(er) techniques, it really is a means of highlight what works, what doesn’t and what problems remain a true challenge for the sector. As discussed in part I, GDC in 2024 was a solid reminder that navigation is still a huge issue - with different studios all vying to address similar issues in different ways, often driven by the games they were making.

Highlighting these challenges is important not just so old men can yell at clouds, but for developers new to the sector to understand not just why these are issues, but the collective efforts made to address them. The new talent emerging in the space, who perhaps have broader views of AI as a whole, may be able to look at other approaches and dive into that sense of experimentation

And lastly while I haven’t placed much emphasis on this throughout this piece, it is worth highlighting the importance and value of academic events. Wind the clock back 20 years ago and there was fundamental misalignment between what AI researchers were interested in, and the problems the Game AI community was trying to solve. This has since been mitigated to some degree, and credit to the likes of the IEEE’s Conference on Games (CoG) and AAAI Artificial Intelligence for Interactive Digital Entertainment (AIIDE) which have expanded and deepened their industry connections in the past 10 years. Bringing interesting work happening in the games space to that audience, and allow for more opportunities for cross pollination.

But it’s not just the platform and the audience, these events are affiliated with academic publishers who understand the importance of collating and sharing knowledge. Sure, these also their problems - again with paywalling and difficulty to engage for emerging talent - but as a resource for consolidating knowledge they are very useful.

At this time, I can only really think of a handful of platforms if I want to learn about how Game AI works, with a particular focus on our corner of the industry, that are currently still active/in print:

The Game AI Summit at GDC.

The Game AI Uncovered book series edited by Paul Roberts.

The industry tracks at academic events

IEEE CoG, AAAI AIIDE, Foundation of Digital Games (FDG) and the Artificial Intelligence and Games Summer School.

The AI and Games YouTube channel.

The AI and Games Conference.

I mean, if you can think of somewhere I’m missing please let me know. After all I just listed eight venues, of which I run and own two of them, and I have contributed to all of the other ones except AIIDE in the past decade.

Finding Relevant and Useful Information

While we have avenues for knowledge to be disseminated, they are finite and they are few. And this brings me to my second issue, though it really is a compounding of the first, in that by limiting the number of avenues through which we share information, it means that often misleading or simply inaccurate information is then spread around more widely.

Finding What We Need

We live in a modern age of widespread information access. The internet has led to a bounty of information that is often repurposed and recycled in various ways by different businesses and individuals to suit their own needs and interested. I mean, after all, that’s what the AI and Games YouTube channel is all about isn’t it?

But given the size of the internet, and the limited number of distribution avenues, and the aforementioned culture of being somewhat reticent in speaking out publicly. It leads to situations where developers simply don’t know what to look for, and where to look for it. While we are in this supposed nirvana of information access, we have all the issues that came alongside it as the internet ages: dead links, search engines that prioritise the wrong thing, SEO increasingly driven by large LLMs that don’t understand game AI because it’s written about so infrequently that it doesn’t really grasp it.

Even just this week in various Discord communities I have seen several game dev professionals looking for:

Information on specific tech stacks to help them learn more.

Talks about the development of specific titles, if they even exist.

Copies of book chapters/papers/talks from out-of-print publications or closed-down events.

Now thankfully given we have communities such as my Discord server, or the Game AI server ran by Paul Roberts for Game AI Uncovered, we have small pockets where devs can share links and resources if and when they find them.

But even then links become dead, including the many sources I point to in the description of my YouTube episodes. As a result I now horde a treasure trove of talks, book chapter PDFs and much more besides, given I don’t trust any of these repositories to keep up this material from one year to the next (and I don't publish them because technically I don't have the legal right to do that).

Ensuring that Information is Relevant

But also by having such widespread access to information, it means that we don’t just need to ensure it remains online, but that it is relevant. A lot of what is out there is not necessarily reflective of how the industry works given the reluctance to publish, and as the tools and technologies we use in game development have become increasingly democratised, it has led to more hobbyist devs dominating those conversations.

Now I don’t say this to speak ill of hobbyists and the like, but there’s a distinct difference between working as a professional game developer and working on your own hobby project. The internet is filled with video tutorials, breakdown guides, and much more besides from people who want to explain how to build a feature for their game. Often creating a little demo in Unity or Unreal and then pushing that out to the masses.

Don’t get me wrong, this is valuable, and it really helps people new to the space to get started, but it needs to be balanced alongside works from professional developers on how these things are built and shipped. There’s a significant difference between a small Unity demo and a shipped title (be it indie or AAA). Given you’re thinking more about how this all aligns with other teams, fits into performance budgets, and delivers on the final product. The very same issue that plagues so many generative AI demos that insist they're the future of game development.

I recognise I am/was part of this problem, given I started on the outside as a hobby dev and educator. But have since been credited as a video game programmer, designer, and consultant on several titles. Naturally everyone starts somewhere, but quite often the experts do not lead the broader online conversations.

Combating Misinformation

A small but critical point is that given how the industry has failed to engage with the broader audience feeds, we now exist in a world where people fundamentally don’t understand how AI works, and that we use different forms of the technology for various purposes.

My earlier point of hobbyist content supporting our knowledge exchange only works if it is to a degree correct, accurate, and reflective of the industry. It’s a point I’ve been very careful of over the years, given the works I create always have a key source aligned with it - be it a book chapter, a talk recording, or a conversation with a developer or researcher. Meaning I can point to that source and say ‘this is why I know this to be true’. I mean that’s because I come from an academic background where you are bred to instinctually back up any assertion I dare to make, but I’m aware a lot of people don’t have such issues.

Our Over-Reliance on the Individual

Pardon the brief sojourn, but one of the most rewarding and fulfilling aspects of my work, is that in the past 2-3 years I have began to understand that the work we do on AI and Games has had an impact on the video games industry.

When I started making videos on YouTube, I was a university lecturer and researcher, and was trying to build something of value for my students. I wanted to create a resource for them as they aspire to enter the games industry so they could learn more about how the experts make this stuff happen - be it in commercial games or academic research. Of course I made the videos public because I figured why not let other people get a chance to learn as well? I’m not a fan of paywalls. While this has since proven somewhat successful, I made content for maybe three years before a larger audience began to find my work, like it, and subscribe for more.

Now I never felt like my career was going to be a full-time content creator, because this field is a niche, and it would never achieve the same popularity as other game development YouTube channels. But we started seeing significant growth in the channel, and it was clear there was something of value here. But how do you make that commercially viable? Since around 2019 when AI and Games became a business, the focus was on on building around it to create something more economically sustainable. When I started running AI and Games as my full-time job back in 2022, I came to realise just how many game developers actually watch my work.

Attending GDC for the first time was a real eye-opener for me: attending the AI Summit and meeting developers who knew me, and my work, and found it useful. The parasocial relationship that being a ‘content creator’ (ugh) brings is that you never really understand who your audience is. I knew a lot of gamers watched my stuff, and that students and aspiring devs did as well, but the passage of time - as students became developers - and in particular I think COVID lockdowns, led to an exposure to my work in the games industry itself that I never anticipated.

It’s why when my friends and I formed Game AI Events CIC and wanted to run our industry event in London, we called it the AI and Games Conference. Because while we are equal owners of this enterprise and are committed to delivering something that is of benefit to our community, we agreed that it was a sensible gamble to put that name, and that brand on our event, such that it would grab the interest of the people we wanted to attend… and it worked!

And so bringing it back to the start, knowing that what I’m doing here - regardless of how in recent years YouTube has continued to kill our channel’s impressions and de-emphasised our content in service of short-form video - knowing that it brings value to game developers around the world is one of the most rewarding things I’ve ever achieved in my career.

I will stress, with all the Scottish emphasis this warrants, that I am really fucking proud of this. I will continue to work hard to earn the trust and faith you have put in me to deliver to the best of my ability so long as I’m up here doing my thing. Thank you everyone out there for the support you have given me and my work over the years.

But by that same token, it scares me that my work has this impact, and that speaks to the broader themes of this issue.

First it re-affirms my earlier points about knowledge in the games industry being fragmented, paywalled, and often lost. In the grand scheme of things, I’d argue more than 70% of my videos are my summarising research papers and conference talks from all around the world that are often paywalled or hidden. AI and Games’ editorial mandate since the beginning has been to provide accessible and entertaining on-ramps to complex subject matter. That’s always been the vision: take complex stuff and make it accessible to people who don’t (yet) understand or appreciate it, and make it digestible and engaging. It’s what makes every episode as much of a challenge as it is a joy to put together. No two episodes are the same, and it’s a new puzzle for me to unpack every time.

But secondly it brings me to the third argument of this piece. If how we consolidated and shared knowledge was achieved more successfully, I wouldn’t be in a job.

Individual Endeavours

As we’ve discussed already, one of the biggest challenges we face is in ensuring the right content is made available, given as I’ve described, game AI is a very specific field, and while you can consume a lot of material on AI more broadly, it helps to learn more specifically about the tools, techniques, and challenges faced by the field.

The problem with game AI being a niche is that pretty much any valuable resource is often at the whim of just a handful of people. You then have to deal with the reality that these people are individuals, with their own interests, priorities, and issues.

Please note a content warning in the following segment for death and sexual offences.

Even big events like GDC, where historically we’ve had the likes of the AI and ML Summit, only work because there are advisory boards that volunteer their time for free* every year to curate the programme, support the speakers, and help define a sense of community in that space. Sure the event is owned and ran by Informa but it relies on the advisors to help steer that content and editorial given they don’t know anything about the subject matter. Make no mistake, the reason that the Game AI Summit has survived in recent years given changes in personnel and the COVID pandemic, has been the drive by the advisory board and many of the long-time attendees to try and retain and equally rebuild the community built up around it.

* In return, advisory board members have historically received an All-Access Pass to attend the conference. All other expenses are their own.

And it’s important to understand this because of how quickly things can shift when there’s a personnel change, because it is rarely the case that those involved actually own the publications we rely on, but they have a significant impact on that space.

We’ve now went through three rounds of game AI books in the past 20 years, with AI Game Programming Wisdom and Game AI Pro - both edited by Steve Rabin - no longer being published and also out of print. Currently we have the aforementioned Game AI Uncovered from Paul Roberts. Plus it appears there will be a change of ownership for the AI for Games textbook since the author, Ian Millington, sadly passed away.

Plus what happens when events implode or die out? It really depends on the ownership. The AI and Games Conference is a successor to the Game AI Conference and later nucl.ai that were owned and operated by Alex Champandard. After trying to make it work for several years, he decided to move on - a real shame given the community that had formed around it. There was an effort to revive it with Game AI North in 2017, but it only ran for one year. After which nothing occurred in Europe until our own event in 2024.

Meanwhile the AI Summit at GDC went through a period of upheaval starting in 2018 - but largely survived given it’s owned by a larger organisation. One of the founders of the summit, Dave Mark, was hit by a car in San Francisco during GDC 2018 and was later hospitalised. He later used his injuries and ongoing rehabilitation as a smokescreen to step down from the AI Summit when in truth Informa had opted to ban him from attending after they became aware he had multiple convictions of child pornography and is a registered sex offender in the United States. With this only becoming public knowledge in 2020 - the same year I joined the advisory board.

Plus I write this in December of 2025 where GDC is going through their ‘Festival of Gaming’ rebrand where the summits now only really exist in name and the experts who have steered it no longer have any meaningful input.

The advisory boards for the GDC summits have been dissolved, with myself and my colleagues invited to stay as ‘summit chairs’ for 2026. This was, as argued by Informa, meant to make our lives easier as we have less work to do in curating the event, but in truth it has created nothing but confusion and frustration as what little editorial oversight we had was removed - not to mention our ability to support speakers to deliver their best work at event.

If you like at the current list of ‘game AI summit’ talks posted for GDC 2026, it is not an accurate reflection of what game AI actually is - with a mishmash of generative AI and sponsored content littering the schedule.

I would argue that the advisory board has fought to retain the identity of the AI summit for as long as we could. I personally have had long email threads with organisers in Informa at about what this community needs in recent years. It was only a year ago when they tried to stuff the AI Summit full of generative AI content, leading to a lengthy correspondence in which I had to explain to GDC’s production team what Game AI is and why it is still relevant; insisting that if they want a generic space for anything Generative AI to make a summit for it. This is what lead the ‘Game AI Summit’ rebranding in the fall of 2024.

So this speaks to a couple of issues:

Over-reliance on individuals can mean what little we collate can fall apart all too quickly if they decide they step down.

We have a number of individuals working to address this, but quite often in isolation.

Even when we have broader editorial oversight to a larger platform, without any ownership to control how it is governed it leads to standards being threatened by commercial interests.

AI and Games really came into its own because there was a vacuum, but I would argue I was the first of our community to try a different approach. Champandard and Rabin’s work is aimed at game AI developers, whereas mine is aimed at students and the public but with a lens to still have value to devs. I think it’s what makes my work stand out to a degree.

But I’ve been doing this for over 10 years, and not only have I contemplated stepping down more than once - largely due to fatigue and frankly investing a lot of time into something that doesn't pay well. I've since had to ask myself, what becomes of all the videos, blogs, notes and resources I’ve accumulated over the years once I stop?

Sure, someone will no doubt step up to fill that void, but how many times do we need to keep doing this? To have someone start all over again?

Right now I’m thinking about how I ensure when I walk away from all of this that the materials AI and Games has curated - particularly for episodes that only exist because we did the research, or interviewed the developers - are going to be properly archived for others to find in the future.

It’s difficult to build an ongoing collective that shares in a desire to do the right thing, and to stick to it. But I feel we need more collective efforts, that are financed by the industry itself, to consolidate knowledge in ways that we might find useful.

We founded Game AI Events CIC - the non-profit that runs the AI and Games Conference - with the intent that one day we hand it over to the next generation. Whether that works, I don’t know yet, but as much as my friends and I are committed I making this work, we recognise that one day we will stop. We will move on. And it would make sense to them hand it over to a new generation of developers to take on that task.

Shifting Trends in Education

A critical point to make, and the penultimate one of this piece, is that we’re at a stage where when someone goes to college or university to learn about artificial intelligence, we’re at a juncture where what is being taught is beginning to shift.

As I mentioned in part one, symbolic AI has been around for a long time both academically and practically in games. But as machine learning becomes increasingly in vogue, it’s changing not just people’s perceptions of what AI is, but also how educational establishments treat the subject.

Game AI relies on students having a good understanding of core computer science and symbolic AI principles: of algorithmic complexity, search and sort algorithms, heuristic design, state space construction, knowledge representation and engineering. A whole bunch of issues that aren’t as prevalent when getting to grips with machine learning. Even more so now as tools for training and deploying ML models become commonplace.

And this adds on to the existing issues there are of teaching Game AI. A lot of academic staff who don’t have games industry experience are familiar with symbolic AI, but don’t understand the intricacies of how it works in games. Heck, AI and Games exists given I was trying not just to educate my students, but reinforce my own knowledge on the subject area.

I’ve met students and graduates whose entire understanding of AI is machine learning based, and when I talk to them about symbolic AI it seems foreign to them. Heck, it was but a few years ago I was teaching the year 2 ‘Introduction to Artificial Intelligence’ class at King’s College London where students already knew how to train an ML model, and wondered why I wasted four weeks of their semester teaching them constraint solvers and planning algorithms.

Now let me stress this is not a criticism of the students, but rather a reflection not just of how universities treat the subject, but of how society approaches it as well. In the past 5+ years the world has had to build a stronger grasp of what AI is. I don’t think it’s done a particularly good job, but by and large people understand the implications of how ML - and especially generative AI - are built on models of data and interpret that data for their own purposes.

Add to this that governments all over the world now have initiatives of some sort to drive AI growth, whatever that means, and more often than not an aspect of that is education. And again, it’s education about what is in vogue in the subject area. I have met with government departments on AI in the creative industries in recent years and trying to re-affirm to them that we need traditional computer science and symbolic AI backgrounds and they look at me utterly confused.

Now don’t get me wrong, I believe in giving students a grounding in machine learning and generative models given that is where a lot of current AI innovation is headed, and of course we have embraced these technologies in various ways in the games industry. This is useful given of course my earlier point in part one about the need to continue to experiment.

But having observed these trends for the past 10 years, I increasingly see it to be the case that Game AI is becoming part of the more ‘archaic’ form of artificial intelligence, to a point that our expectations of what graduates should know in relevant areas of computer science to take on junior roles may prove challenging.

And that brings me to my next point, in what happens when those juniors then seek to progress?

From Entry Level to Mid

My last point to make here is short and sweet: we have a lot of useful information out there in books, in conference talks, online courses, video tutorials and of course my own work that is aimed at introductory levels.

We have become very good at writing introductions to support people entering the space. As mentioned already this is very much AI and Games’ bread’n’butter. For many my videos and articles are the introduction to concepts that people later explore on their own in more detail.

But how do we then get them to progress to the next stage of their careers?

We need more materials that dig into the advanced aspects of game AI, or at least reflect how developers transition from supporting the development of a system designed by seniors, to designing systems of their own.

This is something that is admittedly outside of my own wheelhouse. I have not led game AI teams to a point I would be comfortable building this. But it is a concern I’ve heard raised from others in the space, wondering what answers there are.

Heading into the Holiday Season

Well then… how do I wrap all of this up in a lovely holiday-themed bow?

The Game AI Existential Crisis series will continue into 2026. I suspect we have one or two more chapters of this thesis before we wrap it all up. Once again a big thank you for reading these articles, and I look forward to having conversations on this going forward.

As suggested at the top, this is the last of the big and meaty AI and Games issues for 2026, as we’re going into hibernation at the end of this week. I really need a couple of weeks away from the computer.

But fear not, we still have two more issues coming your way. Our AI and Games GOTY 2025 list is dropping over the next two Wednesdays. Meaning you have a healthy dose of our witterings in your inbox on Christmas Eve, and Hogmanay - New Year’s Eve for all you non-Scottish folk out there.

Shraddha and I have compiled our top 10’s each and are going to share our musings. Amazingly, each of our lists are 100% unique, with zero overlap. So that was quite exciting.

So yeah, tune in next week for #10-#6 of our respective GOTY lists. We have quirky indie titles, big AAA releases, and even some games that came out in 2024 (because that’s how we roll).

![Game AI's Existential Crisis [Part I] | 29/10/25](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!ERGx!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F069186f0-5ef7-4ced-962a-70af65c071e5_3840x2742.jpeg)