Ubisoft’s ‘Teammates’ Demo & Their New Generative AI Push | 26/11/25

The demo I've been waiting for a studio to build since 2023.

Ubisoft lays out their new generative AI technology stack.

I walk through my experiences playing the ‘Teammates’ demo.

Does this herald a new era of gen AI powered gameplay?

The AI and Games Newsletter brings concise and informative discussion on artificial intelligence for video games each and every week. Plus summarising all of our content released across various channels, like our YouTube videos and in-person events like the AI and Games Conference.

You can subscribe to and support AI and Games, with weekly editions appearing in your inbox. If you'd like to work with us on your own games projects, please check out our consulting services. To sponsor, please visit the dedicated sponsorship page.

Hello one and all and welcome back to the AI and Games newsletter. As I mentioned last week, I was travelling to Paris when our previous issue hit your inbox. But what was I doing there, and why?

While I did take the opportunity to enjoy the culture and cuisine, the real story was I had been invited to a press event organised by Ubisoft. A sneak peak as to the company’s aspirations as they continue to explore generative AI, complete with a game demo that embraced the technology in new ways.

It was the generative AI demo I’ve been waiting to see since the hype kicked off in earnest in early 2023. And while it certainly achieved its goals, and left me with plenty to think about. What impact will it really have in the broad scheme of things?

Follow AI and Games on: BlueSky | YouTube | LinkedIn | TikTok

Ubisoft’s ‘Teamwork’ Demo & Their Latest Push into Generative AI

Last week I spent a couple of days in Paris at the behest of Ubisoft, and I had a sneaking suspicion, before the NDA was signed and the briefing information was provided, that I knew what this was going to be about.

Ubisoft have been working on their own internal pipeline and toolset for the adoption of generative AI into their games for the past couple of years, and knowing that the bulk of that work was being led by a development team in their Paris office made it all that much easier to connect the dots.

What followed was a day of presentations and conversations on how they had expanded on their original ideas presented at GDC in 2024, plus a 30-minute demo of a first-person shooter in which players worked their way through a series of combat scenario and puzzles with three different generative AI characters engaging with you throughout.

So to paint a picture of this, we’re going to discuss a bunch of things:

What Ubisoft originally presented back in 2024.

What does version 2.0 of this broader technology/philosophy look like?

A walkthrough of the demo experience and the systems at play.

My discussions with the developers about generative AI integration, and the concerns and issues that raised.

The long-term viability of this approach, and my overall sentiments towards it.

Disclosure: Ubisoft covered my travel and accommodation expenses for attending this event.

The NEO Demo @ GDC 2024

At GDC 2024 I was invited to try out the NEO NPC project behind closed doors. NEO was Ubisoft’s first attempt at exploring how generative AI can be utilised in video games. In a manner akin to the works of AI start-ups such as Convai and Inworld - whose demos I tried out in 2023 - this would focus on interactive non-player characters (NPCs) that engage in conversation and real-time dialogue.

In the original demo, players were sat in front of three scenarios in which NPCs were engaging in dialogue relevant to an objective or aspect of mission design. There was no broader gameplay, but it was at least framed around a particular conversation point, which helped try and keep the situation relevant and focussed.

While NEO wasn’t a particularly immersive or engaging experience for me personally, it was the first time I had seen a game developer attempt to create one of these genAI-powered NPCs, and while I found it lacking, there was at least something going here where I could see a long-term vision.

I discussed this not long ago in part one of my existential crisis essay, in that I find these chatbot demos really bland, given they focus purely on the linguistic aspects and not the broader game AI considerations - I’m far more interested in how we turn language into gameplay, than having a conversation. That said, I did think NEO was the best of those that I tried in that 2023-2024 window, because the demo had a lot of the smaller game design flourishes akin to how Ubisoft goes about building games You could tell this was a games company exploring (generative) AI, rather than an AI company exploring games. You can read my full write-up, or check out the video above which summarises my thoughts and shows footage of my playthrough of the demo.

I had some interesting conversations with some of the developers at the demo event, and recall a number of things that made me feel optimistic about the direction it was going in. For one, they acknowledged the demo was a very early stage prototype, the end result of a mere 3 months of work. That regardless of the impressions made, this project still had a long way to go before anything it produced was ready to showcase in a more meaningful way.

The second big takeaway for me was they had recognised very early on that it needs significantly more work from areas of the development team that the narrative would suggest this technology is replacing. The 20-30 minute demo was the end-result of two narrative designers working full-time on the project for that three month window, writing a large swathe of content at high quality to ensure the universe they had established held up. Scaling that up to a longer experience would require significantly more work both in narrative design, but building broader systems to support personalities of characters and histories of interaction.

Introducing Version 2.0

So here we are just over 18 months since that demo, and myself and a collection of journalists had been invited to check out what was the next significant iteration of the technology at one of Ubisoft’s offices in Paris.

Starting with a presentation from Xavier Manzanares, he explained that the team had spent the last 18 months iterating, expanding, and refining both the technology and the process in a number of ways:

The team had scaled from the original demo staff of around 25, to a team of just over 80.

The focus had been on refining the processes of how generative AI can interface with existing work, be that design methodologies or technology such as game engines.

There was a broader aim to move towards building a toolkit (i.e. a middleware), comprised of trained AI models, expertise, and APIs that would allow for developers on Ubisoft’s game projects to start considering how to interface these tools into their systems.

The event was seemed aimed at cementing the intention that Ubisoft has in showing how generative AI could (not necessarily will) be adopted in their projects - a point echoed by the company’s CEO Yves Guillemot as he stated during the recently delayed earnings call that it will bring a “revolution” in game development. This was bolstered courtesy of a new demo, codenamed ‘Teammates’, that focussed on how this AI tech stack can be integrated into a more traditional Ubisoft-style gameplay experience. This demo was a first-person shooter where you have two assisting NPC companions that you can communicate with, plus a separate ‘overseer’ AI system that supports your gameplay experience. With the demo concluded, we heard again from Manzanares of what they hope to achieve in the 12-18 months.

We’ll dig into the broader aspirations shortly, but first let’s talk about the tech, and the demo that showcased it.

The Technology

The previous iteration of this project was, if I recall correctly, utilising Inworld’s tech stack; building a scaffolding around it such that it was more practical both from a game design but also player experience perspective. However, this new version was an effort to start building their own generating AI pipeline from scratch such that they can start crafting a middleware that can be shared out across different studios.

This makes sense given I suspect in the long-term the ambition is to rely less on external vendors. After all Inworld for all its posturing - and significant investment - has largely abandoned their ambitions to be a NPC chatbot vendor, with their messaging moving towards AI voice models for enterprise markets - which can still be used in games of course. All that said, as I discovered later in the demo, this ambition is still to be fully realised, but it was clear in Manzanares’ closing statement that this is part of the next years worth of development.

Returning to the tech, the team had moved towards standardising the toolset such that it can be interfaced into a variety of different games, with the Teammates demo being indicative of one approach you could take.

What was presented as the broader technology of the middleware amounted to the same as before - an STT > LLM > TTS system - but with a particular focus on how to interface it with gameplay and critically with in-game interactions, NPCs and broader narrative design, as well as game AI systems.

Speech-to-Text (STT) allows the user to provide vocal commands to the game. This is processed from speech, to text, and prepared for analysis and processing.

A Large Language Model (LLM) is processing that message to identify a number of particular aspects:

What is the appropriate written (and later spoken) response to the input.

How does that input map to specific aspects of game such that it can respond to it in kind.

Process the relevant parameters of an input such that it can be passed into gameplay systems to respond to.

A Text-to-Speech (STT) system that then responds in dialogue (and also with subtitles on the screen).

The unspoken part, that is personally for me the most interesting, is that there needs to be a way for all of this to interface with the game, but ideally without disrupting the traditional processes that are used to make said game. While we don’t get any clear indication of how this works, I would surmise that the middleware is built such that API hooks are available to interface with specific aspects of the game itself. Hence when a particular request comes in, this information can be parameterised into an action for execution somewhere within the game. Be it to change an option in the games settings, provide a reactive tutorial to how a particular feature works, have an NPC respond to dialogue spoken at them, or queue up a series of actions, and much more. But in addition to this, the system is also paying attention to what the player does as they play. Hence the characters are responding with exposition, dialogue, and even achievements, based on what is happening. This will all make sense in a moment, when I explain how the demo works in practice.

There were three things that stood out the longer that the discussion surrounding the technology was communicated…

Enhancement, Not Replacement

The first thing that became apparent was that none of the (obvious) red flags people might consider with generative AI demos was apparent. The studio had scaled up a team to build this, and the focus had been on figuring out how to achieve a desirable level of quality without compromising on the personnel behind it. The narrative team had been expanded to handle the increasing challenge of maintaining broader world and character consistency. With narrative director Virginie Mosser expressing that there is a broader misconception in the AI hype that LLMs would make this process easier. Instead, as explained it lead to much more of the traditional ‘bible’ of content for each character being exposed to the player, and that lead to additional challenges. Meanwhile narrative designer Anais Desfachelles stated that having an LLM support the story generation - and also how NPCs interact in that world - adds all sorts of challenges given you want to allow creative freedom while still keep the guardrails of the experience intact.

During the panels that took place throughout the day, the focus was much more on how existing game specialisms can interface with this proposed change to how a game is built - with an AI interface connecting to many systems, based on their experiences building the demo. I would’ve killed for a game AI programmer or designer to be in those conversations, given that was to me the most interesting overlap. That said, a thank you to the PR team who ensured that when I played the demo, I was paired up with Emmanuel Astier, the tech lead on the game, who politely addressed the 101 more technical questions I had throughout.

We’re Still Using External Tooling?

One thing that did catch me by surprise was I figured by now they would be doing all of this in-house. Moving away from using the likes of Inworld is one step towards being a serious tool for broader development across the Ubisoft ecosystem. Not just because they own it in its entirety, but to ensure that they minimise operational security and intellectual property considerations that are outside of their control.

However the main LLM stack being used for the project was running Google’s Gemini 2, and on Google’s servers. I was surprised given something of this magnitude felt like a project that would exist within Ubisoft such that they could control it - even if the costs were increased. I suspect that at this time it is these costs that were the issue. When I spoke with the project’s data & AI director Remi Labory, he discussed not just the broader intent to start running local models (the in-vogue topic of 2025), but also to have it all in house. As mentioned already, this was considered a priority in the closing statements of Xavier Manzanares, that they would be keen to start moving towards local inferencing. We didn’t get into specifics, but it seemed clear that moving away from external hosting was considered as a future goal.

This would certainly have helped given the latency was an issue throughout the demo - with the rationale being that the recent launch of Google’s Gemini 3 launch having an impact on server performance, often by an extra second or two.

A Strictly Text & Speech Focus

The final point I noted was at no point did the use of other generative AI tools come into the conversation. Nothing on the adoption of AI art or animation tools, which is of course a broader concern in the games industry as companies of the size and stature of Ubisoft may well be exploring this as a means to replace developers in key roles. There was no indication of this in the context of the demo, given the focus had been on using text, LLM processing, AI voice models, plus some more traditional machine learning for the purposes of creating a novel gameplay experience.

So that end, what is this demo like to play?

The Teammates Demo

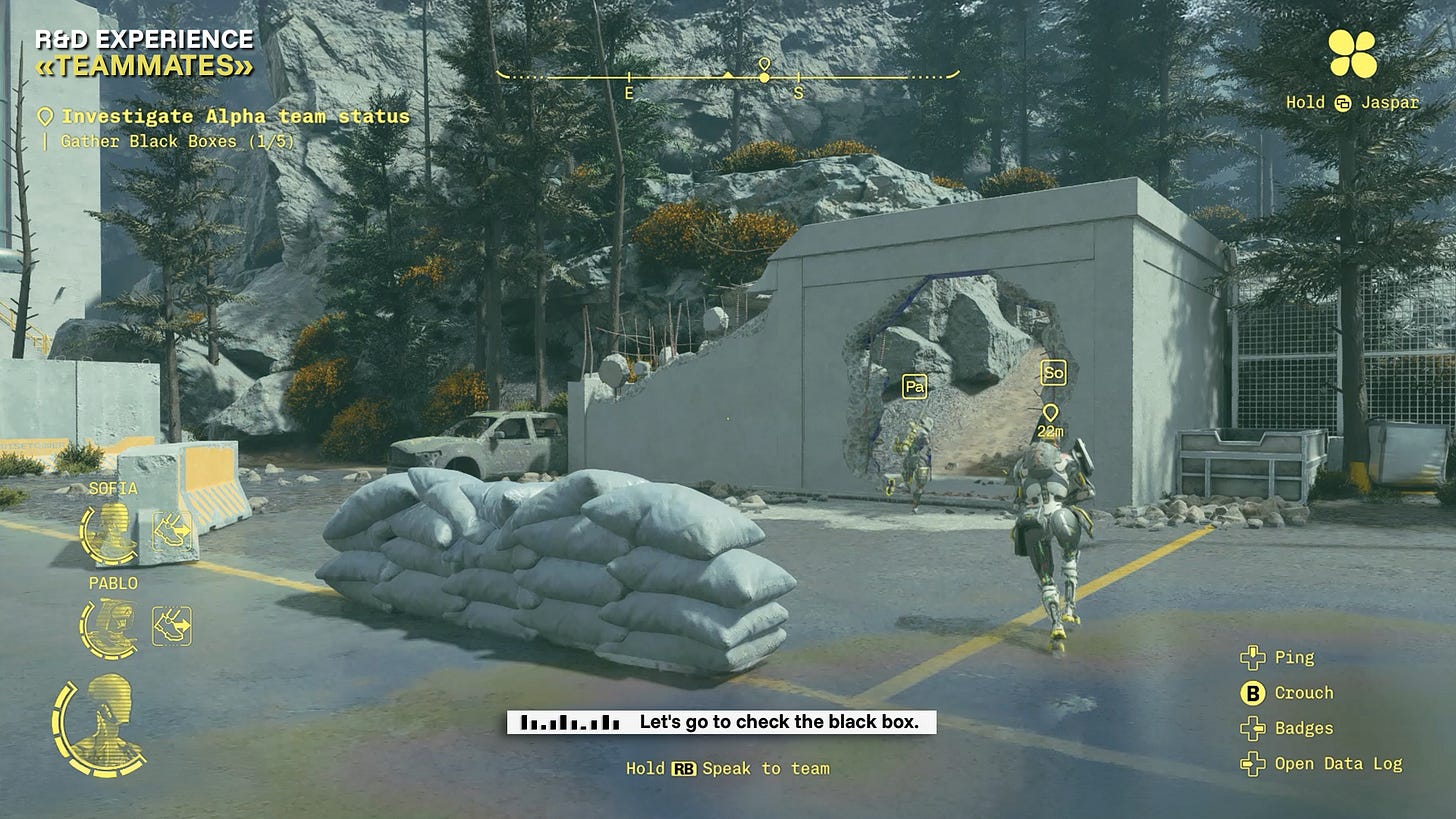

Teammates is a first-person shooter in the Snowdrop engine (used for games like Tom Clancy’s The Division, Star Wars: Outlaws, and Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora) in which the player has to complete a series of objectives with two companion NPCs: Sofia, and Pablo. While in addition to this, you also have Jaspar, a separate AI companion that acts as your ‘guy in the chair’ and provides assistance and support to your experience in a rather self aware fashion. With these three ‘characters’, you are tasked with finding and collecting five black boxes from damaged androids in the map, fighting off NPCs and completing puzzles as you go.

In thinking of a comparison, my first thought is SOCOM on the PlayStation 2 from over 20 years ago. But in keeping with the Ubisoft theme, imagine you’re playing Ghost Recon: Wildlands - a topic we covered on YouTube many years ago - with a first-person mod enabled, and rather than using a ping or action command system to make the ghost squad move around, you can get them to act solely via your voice.

In fact, anybody remember Tom Clancy’s EndWar? The 2009 real-time strategy game from Ubisoft Shanghai that allowed you to order units by voice command? Okay, if Endwar and Wildlands had a baby, this is it.

Sofia and Pablo: The Voice-Controlled NPCs

Your two NPC allies that help you in the Teammates demo are in fact much more akin to a traditional game AI system, only that you can now command them using voice commands.

As explained to us, Sofia and Pablo are powered by a traditional behaviour tree architecture, and their behaviours are built such that the voice commands are processed and translated into actions that can be executed through it. This makes a lot of sense given y’know, we already know how to design AI NPCs for a game, so why bother reinventing the wheel?

In addition to this, they have the ability to engage, react, and converse with the player courtesy of the tech stack that’s been implemented. They respond to your commands, but you can also ask them deeper questions of their design, and of the broader world and mission history, and they can respond to various degrees of complexity.

The demo has players tell the these two NPCs to solve puzzles - such as both standing on pressure pads or unlocking terminals in unison - to pushing up into position to get ready for combat. The earliest combat encounters in the demo has the player without a weapon. Hence you tell the NPCs how to proceed, be it to push up to specific points of cover, to mark an enemy and await your command to open fire.

It was explained that the characters also have means through which to express information about the game world, and even their own back stories. Though I’ll concede that during my playtime I didn’t really ask the NPCs much about the broader narrative - and that speaks to my general disinterest in talking to them really, a point I’ll return to in a moment. Rather it was about how they respond to me through action during play, and that did prove to be rather impressive.

Context is Everything

So the part of this demo that impressed me the most was that the generative AI layer is processing my voice commands such that it interprets from context - whether it be my in-game view, the area of the map we’re in, or otherwise - on how best to address my request.

So for example, if I tell either NPC: “push up to behind that blue crate”, it understands what ‘that blue crate’ means. This is achieved with a combination of in-game tagging of assets by the level designers, combined with a thesaurus of terms associated with each object. Such that it can understand what I meant rather than what I necessarily said. In fact one time I referred to a pick-up truck as a van, and they still understood and responded correctly.

It’s clear from playing the game - and also from conversations with the devs - that as much of the game world is being tagged such that the NPCs can ‘see’ it, given in an earlier room I asked them what objects where in the area, and they listed all of the props in vicinity - though they did so without looking around, which I consider cheating!

Meanwhile the context being pulled from my instructions has even more layers. Returning to the instruction prompt, it also understands what “pushing up” means in context. Ensuring that the NPC then takes cover on the side of the crate relative to me, and not exposed to any enemies on the other side. This was rather context aware given I later told an NPC to go around a specific object to the left, and told the other NPC to hide on the other side of a particular object. This also has layers to it, given if I return to my truck example, I could give them spatial instructions relative to me (“get to cover behind that truck”) or to the truck itself (“push up to the rear of the truck and take cover”) and it understood what I meant.

This is all rather impressive given - and this just my guess - the generative layers are processing the information such that it can then be fed into an environmental query system (EQS) so that it can determine the appropriate location, and that becomes a parameter to the behaviour tree for execution. So in truth there’s a lot of work going on in enhancing the traditional game AI components such that you can get the most out of them. But when it comes to execution, all of it is still relying on traditional game AI methods.

It was largely successful in practice, with only a handful of cases where it didn’t work as intended. Either there was an aspect of context that wasn’t grasped - given I was often deliberately vague to see if they understood me - or there was a small thing in execution that didn’t make sense to the human observer. For example, in the screenshot above there are two pressure switches on the floor, and when I stated “okay, get on those switches and let’s get this door open”, they opened the switches on opposing sides of the room - crossing each other in the process - rather than simply going to the switch closest to them.

The other time this didn’t work as planned, was when they ignored your instructions. As it was explained to me, sometimes the NPCs will ignore your actions should they prove detrimental to them, or they will modify them. So in some situations when I told them to push up, they went to the original location, only to change to a more tactically advantageous position (so that they don’t get spotted, or have clearer line of sight). In other cases, they ignore it because it puts them in danger of being shot by enemies. However, this wasn’t communicated very clearly when this happened, and it seems like an area of the design that warrants improvement.

Waiting to Attack

In addition to these context sensitive interactions, the NPCs are also capable of processing and responding to instructions that have layers of complexity to them, with a requirement of concurrency, or simply awaiting the appropriate signal. You can given them multiple instructions at once (“both of you push up to cover near your closest enemy, and mark them, when I open fire, you’re free to take them down”), and they execute them in sequence and will wait for any corresponding go signals when necessary.

So it’s not just executing actions in the moment, it’s able to queue up actions and execute them in sequence, and wait for the appropriate instructions in specific circumstances. There’s also an aspect of concurrency, in that I could have both Sofia and Pablo execute actions at the same time as part of the same instruction, and even customise it for each.

Jaspar: The AI Assistant

Meanwhile, on top of all of this is a separate in-game AI companion called Jaspar. Think of this as like a sassy and wise-cracking AI assistant that responds to your requests to provide information, and change your gameplay experience. I assume the name is a deliberate choice, a spelling of ‘Jasper’ which in its original meaning is roughly ‘treasurer’, so like a keeper of knowledge and wisdom? Also it isn’t too far away from that um, other, well known AI-based voice assistant in contemporary fiction.

There is a notable difference in the ‘personality’ behind the Jasper agent versus that which controls the two NPCs. The dialogue and the delivery of said dialogue by Sofia and Pablo is rather robotic, which makes sense given they’re robots. Whereas Jasper is more cocky, making humorous quips about the situation and trying to be much more of a personable character to interact with. Jaspar’s job is to support you during the game, both to remind you of what you’re doing but help you interface with the demo as best as possible.

“Let Me Fix That For You…”

As you start the demo, Jaspar introduces himself, asks for your name, and then proceeds to explain how the demo works, and some of its capabilities as this supporting AI agents. It explains early on it can highlight objects in the HUD for me so I can find them more readily, as well as explaining how a pressure pad for a door works - I told Jaspar I didn’t need the explanation, to which his response was a little catty.

When prompted to stand on the plate and open the door, I asked how I was supposed to do that, Jaspar responded by stating “you move silly”. However I told the system I wasn’t clear on how to do that, and in doing so it raised the controls menu and gave me a brief overview of how to play the game in my chosen format of mouse and keyboard.

While Sofia and Pablo had the gen AI stack hook into game AI systems as well as narrative design, Jaspar is hooked into the rest of the game. Hence I could ask it to remind me of objectives, highlight enemies on my HUD, and even change the colour of the HUD overlay to address my colour blindness (it also guessed my form of colour blindness based on my request). It can see everything that Sofia and Pablo can see and then some. There were some navigation volumes indicating that parts of the demo were still in development and locked off. To my surprise Jaspar responded to my question as to why this was there, stating that the Teamworks demo was still in development.

As the demo progressed, it would re-affirm to me my objectives, and offer to summarise the contents of the black boxes I retrieved from the damaged robots in the level. It was a little too chatty for my tastes, given it led to me having to talk to it repeatedly - which isn’t really something I find much value in if I’m honest, but hey, that’s the point of the demo.

A Word on Accessibility

The conversation surrounding Jaspar - and the demo as a whole - when chatting with the other journalists (if you’ll forgive me calling myself a journalist), was about the opportunities something like this creates from an accessibility perspective. Letting people customise their experience on start-up of a game just by talking to it is a pretty powerful thing. Not to mention the capacity to change settings mid-game by simply asking Jaspar to sort it out for you. In an age where AI needs to show it can deliver meaningful improvements to the player experience, this alone is pretty important.

While giving orders to Sofia and Pablo is reasonably smooth - and it only fell over my accent a couple of times - it got me thinking that for all of the accessibility that Jaspar affords, Sofia and Pablo do the opposite. You need to talk to these characters in order to get them to do what they do. There was no alternative control mechanism - like say a smart ping system - to get them to do what you wanted. I think you could achieve a lot of what they do in the game via a system like that, given the voice commands are as I described being translated into game AI execution. But it would mean for any game like this there’s a lot of work to be done in ensuring people who can’t (or won’t) speak to the game are exposed to those features.

Don’t get me wrong, I appreciate the point of this demo is to highlight this conversational-based system, but it highlighted that by forcing games systems to rely on these tools, it introduces new accessibility concerns for other reasons.

Obligatory Ethics Conversation

Last week’s piece on the use of generative AI in Embark’s Arc Raiders stimulated quite a bit of discussion on social media. With BlueSky generally liking my take, while LinkedIn was less than enthusiastic. Gleam from that what you will. So given we’re back once again in the land of trained voice models using real human voices, it’s important we circle back to this issue.

So first and foremost, yes this demo is using human voice actors who provide a tremendous amount of performance to then yield the desired output which is achieved using ElevenLabs (one of the few AI voice generators that one could argue is good). This was a point that the demo’s audio director Romain Brillaud spoke of at length during the panel discussions. That not only do they need talented and expressive performers to embody each of the characters, but he made it clear that the performers need to have control of how their likeness is used, they need to be compensated for usage, and had to be involved in the process every step of the way.

Now how that works, or what they were paid, I don’t know - and I didn’t ask, because I doubt I would get a clear answer on it. But it was a recurring point throughout the conversations we had both in panels and in interviews that the ethical consideration of the technology was being debated and discussed throughout the process.

As brief digression, it’s worth highlighting that, unlike Arc Raiders, this demo needs the AI voice model(s) to respond to the very specific queries and requests of players, responding to them in natural language.

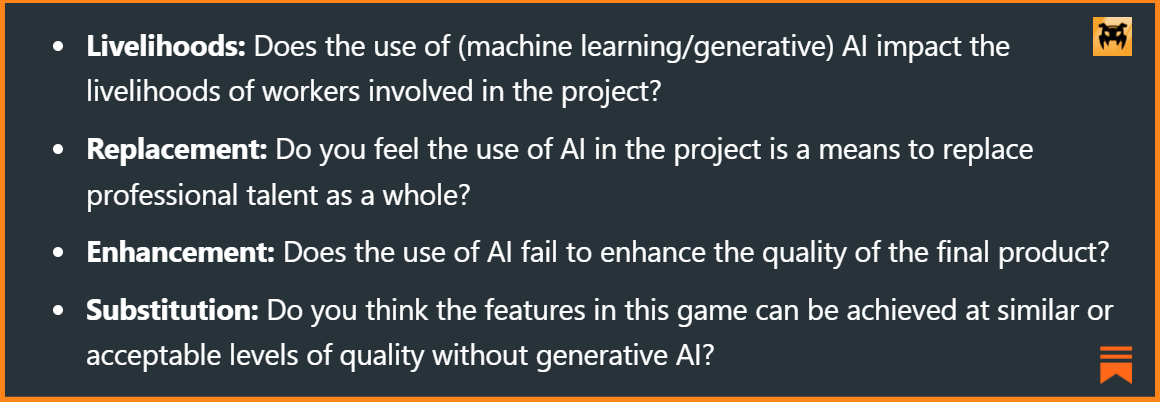

As such, per my rubric of generative AI adoption from that issue (shown above), it passes the livelihood and replacement criteria in that from the beginning they made it clear it needs this technology stack to work as envisaged, but also that they had these performers involved from the earlier stages of the process. It is also passes the enhancement and substitution aspects given you can’t implement the dialogue systems and interaction systems for Jaaspar, Sofia and Pablo without this technology.

So while people may still be (understandably) uncomfortable with it, it passes the four key considerations I raised in that creatives are being respected in a process that inherently needs them to do achieve you can’t do otherwise, and all of it is a critical component of the game itself. Something that Arc Raiders fails to do.

I think for me the big outstanding question, was how whether the voice actors are renumerated in a manner commensurate with other work they would have done for Ubisoft.

When the question arose of how do you prevent AI-generated outputs from feeling lifeless and uninteresting, creative director Reynald Francois stated “AI cannot do art, it can do content”. Embellishing on this by highlighting that AI has no authorial intent and therefore now more than ever it’s important than human creatives inject the intent, and the meaning into the work. I followed up with on this comment during the interviews on how that philosophy more broadly extends to other uses of generative AI. But also how do you foster a culture around accepting and embracing the technology when many people will have visceral emotional reactions towards it?

Francois elaborated that for him it was important that it be driven from a perspective of providing education, and enabling buy-in from personal pain points of professional workflows. Forcing colleagues to explore generative AI wouldn’t work, but rather it had to be seen that it could deliver value by improving a creative process without fundamentally changing it. It speaks to a general comment made by everyone in the panel segments that those who did not come from an AI background found generative AI scary, until it became apparent as to its limitations.

Francois gave an example of when concept artist spends 80% of their time doing research for an idea and only 20% of the time doing art, then their process could be refined. If by using generative AI the research phase could be reduced to 20%, then that would quadruple the amount of time the artist spends in their craft. Rather than forcing the artist to use AI to make art, show them how to use AI to focus more on art.

I’ll give it to him in that it aligns with my philosophies in how we conduct consultancy projects with games studios. I’m of the belief that our goal at AI and Games is to educate, and support studios as they explore these concepts. Should they decide not to embrace it at the end of the process, that’s fine. It’s more important these decisions are coming from more fleshed out and informed perspective, rather than solely an emotional one. I was happy to see we are aligned on this issue to some degree.

All that said, I am still concerned about the broader ethical implications of the technology. For now it seems like everything the team are doing is in pursuit of using the tech to build something new - and they did achieve that. But nonetheless it should be considered a topic of ongoing consideration as these practices evolve, and the broader questions of the impact it has on creatives becomes clearer.

My Thoughts on the Demo

So I wrapped up my time with the demo and started making my way back to London, mulling over lots of different aspects of this. I have mixed feelings about it, both in terms of what was achieved, but also the relevance and value of it in the long run. There’s some really interesting stuff happening, and I think the team did a really good job, but I’m not sure if it’s something I’d like to see in a game in its current form.

Someone Finally Built The Thing

As I said at the top, this is the first time I’ve seen a studio build the generative AI demo I’ve been waiting to see. I’m frankly fed up with seeing so many generative AI demos that have zero substance, because they’re largely about placating investors and hopefully showing off to potential customers, than about showing something of value for consumers. Give me a demo that shows value for players by building something that either enhances on an existing concept with generative AI, or delivers something you simply cannot do without it.

Teammates delivers on both of these ideas, in that it provides a layer on top of a very traditional Ubisoft experience, while also introducing a layer of accessibility that is really quite powerful. Interacting with Sofia and Pablo allows you to play in ways very similar to old school Rainbow Six but solely through voice interaction. The idea of playing a modern interpretation of the older games in that series, or something like SWAT or Ghost Recon, has interesting possibilities. Though as I’ll stress in a second, relying on the voice could be problematic.

For me this was a really interesting project in expanding and fleshing out game AI systems to interface with generative ones. Something I argued for recently in part 1 of the existential crisis essay. What can we do to make game AI more response and dare I say ‘realistic’ in the eyes of the player? By using this as part of that I think we’re onto something quite interesting, and I’m keen to see what other games you could build with this infrastructure. Come on guys, let me consult on Tom Clancy’s EndWar 2 - I know you were working on a sequel like 10+ years ago.

Meanwhile having Jaspar as your video game assistant feels far more interesting to me than what little I’ve seen of Xbox Copilot, given it’s baked into the game and helping me make changes to my experience, or supporting it, in a way that feels congruent and sensible. There was discussion of building out Jaspar’s long-term memory such that it becomes an ongoing aspect of play, and that does sound appealing. Reminding me of what I was doing 6 months ago when I last booted up Assassin’s Creed: Shadows (an issue that occurred for me not too long ago), strikes me as rather helpful. Plus building a profile of your commonly used settings that could transfer from one Ubisoft game to the next would be great. Just invert the Y-axis for me by default please, thank you.

So I do think props should be given to the team, in that I felt it was a useful way to showcase what you can do with this tech in a more traditional gameplay sense.

Exciting Accessibility Opportunities

I do think that perhaps the most exciting aspect of this is from an accessibility point of view. The games industry has in the past decade really began to embrace how important it is to provide a suite of features that make it easier for people to sit down and enjoy games. With so many titles providing great mechanisms to change how a game is delivered to you, as well as tweaking the experience to make it more palatable.

I think having a system like Jaspar more readily interfaced into a console or gaming PC such that people can automatically get the system doing stuff they need quickly and efficiently is really exciting. That as soon as I start a game, I can either tell it exactly what I want, or have it load up features from my previous history in a way that will make that game much easier to pick up and play.

A Labour Intensive Interaction

All that said, I came away from it without much desire to play it again, and that was largely because I had to talk to it. This is not a reflection on anything presented, or the team at Ubisoft - I really think the demo was quite impressive. It’s more of a personal thing.

Personally, I don’t enjoy using voice-based systems, which comes from a perspective of being someone who understands AI technology, someone who often has to deal with language barriers brought on by my dialect (I live in England, and the vast majority of people struggle with my accent, never mind a machine), but also because I personally see no inherent value in talking to a computer.

For me using my voice has to have purpose. I mean I talk for a living. I speak at events all over the world, I present online, I engage in business interactions, but also - my introverted nature aside - I enjoy social interactions with people. It’s all about the rapport and broader emotional connection you can build with people. To me this is really valuable and it’s why I enjoy speaking at events (and of course running a YouTube channel). By that same token, talking to a game is no different than a toaster, I don’t see value.

Now of course I just spoke at length about the accessibility opportunities. Let’s not discount that. Progress in these areas is far now important than my own stubbornness. If the future of this tech is simply Jaspar appearing in every Ubisoft game and I have to tell it to shut up unless I speak to it, that’s perfectly fine. I think that’s a really useful way to embrace AI in the broader journey of making games available to everyone.

But as I mentioned earlier, I didn’t really strike up a conversation with Sofia and Pablo, because I don’t feel the need to engage in dialogue with them. They’re NPCs in a video game, they should be responding to my actions and letting me just get on with playing the game. This is in part driven from their design as robots - which hey props to the dev team for making that click. If I want to know about the game lore, let me read it or expose it to me in a way that is sensible for the narrative (which is of course what narrative designers actually do).

For one, it’s worth highlighting that I suspect there’s a generational component to this. Manzanares stated that the game had also been tested by influencers as well as players over on the UPlay network, and the feedback had been very positive. I’m a guy in my 40s, and so my perspectives on this are coloured by decades of playing games, and having a different relationship with games than someone half my age. I think younger players who have grown up surrounded by Alexa’s, Siri’s and much more besides are more ready to engage with voice-based interaction systems than an aging game AI expert.

But the other issue is that while this works, and is pretty cool, it introduces a challenge that future games should factor in: using your voice is labour intensive, and I don’t think a lot of companies interested in generative AI are thinking about that.

Talking to an NPC and giving it interactions adds a whole layer of cognitive load to a game. Given I’m not just thinking about what I want them to do, but how to express that such that the gen AI stack understands it, and whether what I'm asking will translate into what I want based on my understanding of how the game works.

I found myself having to think consciously of what to say, and how to say it, in a way I wouldn’t with human players. I can trust a human to understand and work around any ambiguity - and of course they have their own agency and skill to take into account.

Now as mentioned this demo does a great job of working around the ambiguity - and I deliberately tested it to see if it could. But it’s more work for me as a player. When we came under gunfire as enemies attacked us, I was trying to speak to the NPCs and it was both difficult to formulate what I wanted to do, but also they didn’t respond in a way that helped me understand that my commands were sinking in.

What Else Can Be Done in Gameplay?

I think the next step for this in terms of gameplay feasibility, is to show me how Sofia and Pablo can react to my actions in the game. By watching what I do, how does that influence their actions? And how do they express that impact to me?

I think there’s real opportunity to build on these systems to pay more attention to my behaviour, my style of play, and have that influence how my companions operate. Suggesting tactical options based on prior experience or perhaps exploiting a feature of the terrain or a new mechanic or weapon. There were some situations where there was a height differential, and having one of these NPCs carry a sniper rifle and offer to take a vantage point to mark targets and trigger the combat would be interesting.

That would both elevate the agency of the NPCs, and minimise my cognitive and physical workload in having to tell them what to do. And again all of that can be ML layers sitting atop traditional game AI tech, and to me that’s very exciting. Running classifiers and behavioural models on the encounters we play, and over time having Sofia and Pablo learn how I like to fight. That would be pretty sweet.

Wrapping Up

Thanks once again to the folks over at Ubisoft for inviting me over. It was a great couple of days, and they took good care of us. It’ s not often I get invited to participate in such things. But hey, it did seem appropriate for this here publication.

As we wrap up, you might think I forgot that this week’s issue was meant to be my previous delayed Meaning Machine interview. Fear not! I did not forget! Sadly Ubisoft pushed up the embargo for the Teammates demo from next week to last Friday, so it made sense to get this out while the likes of GamesIndustry.biz and Video Games Chronicle were writing about it as well.

Next week, Meaning Machine, it’s happening! See you then.